Quelle: dpa

Rahel Weier/Miriam Rehm/Neva Löw, 29.01.2026: How gender attitudes shape climate concerns

Women are more likely to worry about the climate crisis than men. Traditional gender attitudes among men reduce the likelihood of climate concern. The concept of “hegemonic masculinity” explains this gender gap.

Women are more likely to be concerned about the climate crisis than men—this gender gap is clearly evident in the data. It is already known that conservative political attitudes reduce climate concerns, but our analyses show an additional effect: traditional values regarding gender roles also reduce the likelihood of men worrying about climate change. This correlation can be explained by the concept of hegemonic masculinity, which is based on control, a fixation on technology, and the domination of nature – and thus also creates space for authoritarian movements, which can be countered through solidarity and a reorientation of our economic system.

Concepts of masculinity and power relations

The concept of hegemonic masculinity, originally formulated by Raewyn Connell (1990), emphasizes the social link between ideas of masculinity and power. The term was coined in the 1980s and has since been subject to diverse criticism and further development (see Connell/Messerschmidt 2005): For example, the diversity of masculinities and changes in hegemonic notions of masculinity are discussed in academic circles, and an essentialist idea of masculinity is considered problematic. Nevertheless, the basic assumption that notions of masculinity are a power relation, albeit one that is always contested, continues to have great influence and will only be briefly touched upon below.

Connell defines it as the form of performative masculinity that is socially considered legitimate and secures social interpretive authority and priority access to power for those who conform to accepted patterns of masculinity or gender roles. Hegemonic masculinity does not describe individual, actually existing men or women, but rather the widespread ideals, fantasies, and desires (Connell/Messerschmidt 2005). This is how a social order is structured: certain characteristics—such as rationality, independence, a fixation on technology, or access to nature and other people—are associated with an idea of “masculinity” and valued more highly than characteristics with non-masculine or feminine connotations, such as caring, vulnerability, or cooperation. Although this ideal has changed historically and culturally, it continues to shape how we talk about politics, economics, and even the climate crisis (Pearse 2017).

This can be seen in the authoritarian movement in the US, for example, where a specific form of hypermasculinity is rooted in a” lifestyle based on fossil fuels and misogyny (New Daggett 2023: 12). Cara New Daggett refers to this as “petro-masculinity.” This is linked to the active denial of climate change and an active demand for a lifestyle based on fossil fuels.

Eco-feminist approaches have been pointing out the intertwining of productive force development and the patriarchal and colonial project for decades (Barca 2014, Suva/Mies 2014). Empirical studies show that wealthy men in particular contribute disproportionately to the climate crisis through excessive meat consumption, energy-intensive lifestyles, and frequent travel (Räty/Carlsson-Kanyama 2010). However, this is not about assigning individual blame, but rather about the structures of a patriarchal power system that often remains invisible because it is perceived as “normal.” The climate crisis is the result of fossil fuel-based industrialization, colonialism, and an economic system based on growth and exploitation (Merchant 1989). Hegemonic masculinity is closely intertwined with this system: it combines notions of strength, control, and technical superiority with the claim to dominate nature (Pease 2019).

Furthermore, hegemonic masculinity affects climate concerns through various channels. First, climate protection and care are often culturally marked as “feminine” (Brough et al. 2016); those who adhere to traditional images of masculinity tend to distance themselves from these issues. Second, tendencies to justify the system play a role: traditional gender roles are often linked to a conservative desire to preserve existing power structures. Climate policy, which requires change, is therefore more likely to be perceived as a threat and rejected (McCright/Dunlap 2011). Third, research shows that hierarchical values weaken pro-environmental attitudes. This correlation exists regardless of gender, although men are more likely to hold hierarchical values (Lewis/Palm/Feng 2019).

The gender gap in climate concerns

Using data from the Socio-Economic Panel (SOEP) from 2019, we investigated whether the perceived urgency of the climate crisis differs between genders. Specifically, we asked the question: Is the lower level of concern about climate change among men also due to their stronger agreement with traditional notions of masculinity? Climate concerns are relevant because they are not just an attitude, but a key driver of political support for climate policy. If we want to understand behavioral changes and actions related to climate issues, we also need to understand attitudes toward climate change (Albarracin et al. 2005).

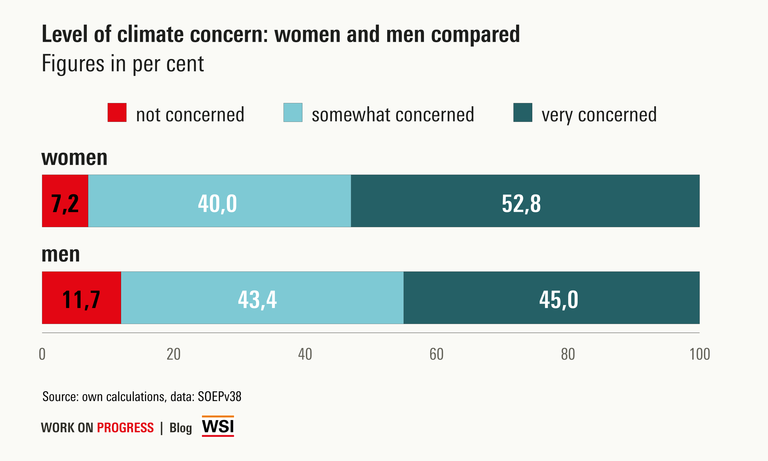

The data in the graph show that when asked what concerns people have about the consequences of climate change, the vast majority in Germany respond with “some or great concern.” Only a small proportion of men and women are not concerned – but this proportion is significantly higher among men (the red sections in the following graph). In contrast, women are significantly more likely to be very concerned about the consequences of the climate crisis (dark green in the following graph). This is often explained by socialization, according to which women traditionally tend to take on caring roles, including towards the environment. However, Strapko et al. (2016) show that this explanation falls short. It can easily promote essentialist notions of the “natural” characteristics of women or men: women are “naturally” more concerned about family and nature and therefore have a biological predisposition to do so – yet gender roles are socially constructed, historically developed, and thus contested and changeable. To understand the dynamics behind the gender gap in climate concerns, we therefore need to look at the underlying structures of social power relations.

Results

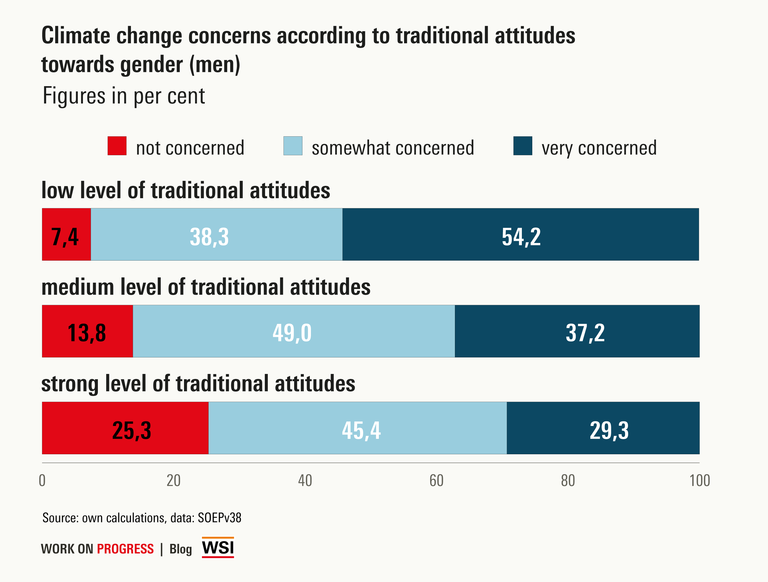

Next, we examine whether lower climate concerns can be explained by traditional attitudes toward gender roles. We measure these using an index of several questions on gender diversity, ranging from 1 to 7. For example, respondents are asked to agree or disagree with the following statement: “It should be accepted in our society that not everyone identifies with their biological sex.” Higher values represent stronger rejection and thus more traditional gender concepts – an indicator of dominance-oriented, traditional male concepts.

Let's now compare the climate change concerns of three groups: men with low, medium, and high levels of traditional attitudes toward gender. The pattern is clear: only 7 percent of men with more progressive attitudes toward gender, compared to 25 percent of those with traditional attitudes, say they are not concerned about the consequences of the climate crisis. The results are similar for women.

To ensure that this trend cannot be explained by other factors, we also control for many other factors in a regression equation that could explain low climate concerns, such as political views, age, education, or income. In other words, we compare people who are as identical as possible, differing only in their gender attitudes. The results show that climate concerns are significantly lower among men when there is greater agreement with traditional gender attitudes, regardless of age, education, income, or employment status. Specifically, this means that if a man's gender attitudes are one level more traditional, the likelihood that he will be concerned about climate change decreases by about 26 percent. In addition, conservative political attitudes and party preferences also have a negative effect on climate concerns among men. Statistically speaking, the likelihood that a man will be concerned about climate change decreases by about 17 percent if he is one level more right-wing politically.

For women, on the other hand, the point estimates are not statistically significant. These data therefore suggest that perceptions of climate change are closely linked to ideas about gender roles, especially among men. For women, however, this correlation cannot be clearly confirmed statistically; other factors may influence the results here.

Implications

Our analysis provides evidence of how power relations influence climate concerns and how gender relations shape identity. Only by understanding and addressing fundamental social dynamics can we mobilize the broad social support needed to tackle the climate crisis effectively and fairly. In our view, this requires a radical questioning of hegemonic masculinity.

A key step in this direction is a societal realignment of our social and economic system toward care and solidarity. Our economic activity can no longer be geared toward profit maximization and expansive access to nature. We must begin to understand caring economic activities as the truly productive activities. This would have to go hand in hand with an upgrading and expansion of care activities. Specific first steps would be to expand childcare, eldercare, health care, and education systems, as well as a general reduction in working hours.

The fact that these visions not only seem utopian at present, but that public discussion is also moving in the opposite direction, plays into the hands of those who have conservative ideas about gender and deny the climate crisis. Right-wing movements in Germany and the US have long been using ideas and feelings about masculinity and gender to mobilize and politicize. This makes it all the more urgent to remove the breeding ground for fascist tendencies by taking measures to reduce inequality and promote emancipation.

Gender equality, social equality, and climate protection are not separate issues, but interwoven challenges that can and must be solved together.

References

Albarracin, D./Johnson, B. T./Zanna, M. P. (eds.) (2005): The Handbook of Attitudes, 1st edition, New York

Brough, A. R./Wilkie, J. E. B./Ma, J./Isaac, M. S./Gal, D. (2016): Is Eco-Friendly Unmanly? The Green-Feminine Stereotype and Its Effect on Sustainable Consumption, in: Journal of Consumer Research 43 (4), pp. 567–582

Connell, R. W. (1990): A Whole New World: Remaking Masculinity in the Context of the Environmental Movement, in: Gender and Society 4 (4), pp. 452–478

Connell, R. W./Messerschmidt, J. W. (2005): Hegemonic Masculinity: Rethinking the Concept, in: Gender and Society 19 (6), pp. 829–859

Lewis, Gregory B. L./Palm, R./Feng, B. (2019): Cross-national Variation in Determinants of Climate Change Concern, in: Environmental Politics 28 (5), pp. 793–821

McCright, A. M./Dunlap, R. E. (2011): Cool Dudes: The Denial of Climate Change among Conservative White Males in the United States, in: Global Environmental Change 21 (4), pp. 1163–1172

Merchant, C. (1989): The Death of Nature: Women, Ecology, and the Scientific Revolution, New York

New Daggett, C. (2023): Petromaskulinität. Fossile Energieträger und autoritäres Begehren, Berlin

Pearse, R. (2017): Gender and Climate Change, in: Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: Climate Change 8 (2), e451

Pease, B. (2019): Recreating Men’s Relationship with Nature: Toward a Profeminist Environmentalism, in: Men and Masculinities 22 (1), pp. 113–123

Räty, R./Carlsson-Kanyama, A. (2010): Energy Consumption by Gender in Some European Countries, in: Energy Policy 38 (1), pp. 646–649

Strapko, N./Hempel, L./MacIlroy, K./Smith, K. (2016): Gender Differences in Environmental Concern: Reevaluating Gender Socialization, in: Society & Natural Resources 29 (9), pp. 1015–1031

The article in German language: Wie Gendereinstellungen Klimasorgen prägen

This blog series is a collaboration between the WSI and the Next Economy Lab (NELA). The WSI Annual Conference 2025 entitled "Crises, struggles, solutions: transformation conflicts in socio-ecological change" also addressed the topic. At NELA, this series is part of the project "Team Social Climate Change" in which trade union members from IG Metall, IGBCE and ver.di are being trained as transformation promoters in a cross-union training programme. They learn how to help shape the social climate transition locally and in their companies, how to win supporters and actively counter resistance. The project is supported by the Mercator Foundation.

The articles in the series

Neva Löw/Sarah Mewes/Magdalena Polloczek: Conflicts over a socially just climate transition (October 8, 2025)

Markus Wissen: Transformation conflicts and global climate justice (October 9, 2025)

Neva Löw/Maximilian Pichl: How the climate crisis and global migration are linked (October 13, 2025)

Silke Bothfeld/Peter Bleses: Equality in the labor market – The challenges of the socio-ecological transformation (October 21, 2025)

Marischa Fast/Stefanie Bühn/Johanna Weis: Health protection in the context of climate and environmental crises – an issue for the world of work (November 27, 2025)

Rahel Weier/Miriam Rehm/Neva Löw: How gender attitudes shape climate concerns (January 29, 2026)

Further articles in preparation

Authors

Rahel Weier studies socioeconomics at the University of Duisburg-Essen and conducts research on climate policy from a gender perspective.

Prof. Dr. Miriam Rehm is Professor of Socioeconomics at the University of Duisburg-Essen. Her research focuses on social inequality, labor economics, gender, and quantitative empirical methods.

Dr. Neva Löw is a research fellow at the WSI of the Hans Böckler Foundation.